Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Save the World by Paul Stamets

Mycelium Running is a manual for the mycological rescue of the planet. That's right: growing more mushrooms may be the best thing we can do to save the environment, and in this groundbreaking text from mushroom expert Paul Stamets, you'll find out how. The basic science goes like this: Microscopic cells called mycelium--the fruit of which are mushrooms--recycle carbon, nitrogen, and other essential elements as they break down plant and animal debris in the creation of rich new soil. What Stamets has discovered is that we can capitalize on mycelium's digestive power and target it to decompose toxic wastes and pollutants (mycoremediation), catch and reduce silt from streambeds and pathogens from agricultural watersheds (mycofiltration), control insect populations (mycopesticides), and generally enhance the health of our forests and gardens (mycoforestry and myco-gardening). In this comprehensive guide, you'll find chapters detailing each of these four exciting branches of what Stamets has coined mycorestoration, as well as chapters on the medicinal and nutritional properties of mushrooms, inoculation methods, log and stump culture, and species selection for various environmental purposes. Heavily referenced and beautifully illustrated, this book is destined to be a classic reference for bemushroomed generations to come. Editorial Reviews Review As a physician and practitioner of integrative medicine, I find this book exciting and optimistic because it suggests new, nonharmful possibilities for solving serious problems that affect our health and the health of our environment. Paul Stamets has come up with those possibilities by observing an area of the natural world most of us have ignored. He has directed his attention to mushrooms and mycelium and has used his unique intelligence and intuition to make discoveries of great practical import. I think you will find it hard not to share the enthusiasm and passion he brings to these pages. --From the foreword by Andrew Weil, MD, author of Eating Well for Optimum Health Stamets is a visionary emissary from the fungus kingdom to our world, and the message he's brought back in this book, about the possibilities fungi hold for healing the environment, will fill you with wonder and hope. --Michael Pollan, author of The Botany of Desire This is the kind of book I love: highly factual and practical and mixed with the spiritual content that sets the great writers apart from all the rest. --John Norris, former deputy commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration and founder of the Bioterrorism Institute This is the first book to give the Kingdom of the Fungi its proper place in the scheme of things. It is the most important book on nature that I've seen in years. --Gary Lincoff, author of National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Mushrooms A paradigm-changing book. Stamets's visionary insights are leading to a whole new understanding of how mushrooms, scarcely seen and rarely appreciated, regulate the earth's ecosystems. --John Todd, founder and president of Ocean Arks International This visionary and practical book should be an instant classic in the emerging science of how to use nature's wisdom and fecundity to rescue the earth and ourselves from the unwelcome consequences of human cleverness. --Amory B. Lovins, chief executive officer of Rocky Mountain Institute This gospel of fungi contains crucial pragmatic solutions showing us how to work with nature in order to heal nature. --Kenny Ausubel, founder and co-executive director of Bioneers In his respectful and casual way, Paul brings depth and clarity to the complexity of fungi and its place in the natural order, all the while engaging us in fungi knowledge for healing our planet. --Guujaaw, president of the Haida Council, Haida Nation Stamets's best work to date, Mycelium Running provides a wealth of information showing how fungal mycelia and mushrooms can profoundly improve the quality of human life. Should be mandatory reading for government policy makers. --S. T. Chang, professor emeritus, Chinese University of Hong Kong From the Publisher A manual for healing the earth and creating sustainable forests through mushroom cultivation, featuring mycelial solutions to water pollution, toxic spills, and other ecological challenges. Mycotechnology is part of a larger trend toward using living systems to solve environmental problems and to restore ecosystems. Covers mycorestoration (biotransforming stripped land), mycofiltration (creating habitat buffers), mycoremediation (healing chemically harmed environments), and mycoforestry (creating truly sustainable forests). More than 300 full-color photographs. About the Author PAUL STAMETS, founder of Fungi Perfecti (www.fungi), has been a dedicated mycologist for more than thirty years. He is the 1998 recipient of the Collective Heritage Institute's Bioneers Award and the 1999 recipient of the Founder of a New Northwest Award from the Pacific Rim Association of Resource Conservation and Development Councils. Stamets has written five books on mushroom cultivation, use, and identification and numerous articles and scholarly papers on medicinal, culinary, and psycho-active mushrooms. His books Growing Gourmet and Medicinal Mushrooms and The Mushroom Cultivator (co-author) have long been hailed as the definitive texts on mushroom cultivation. About the Author PAUL STAMETS, founder of Fungi Perfecti (www.fungi), has been a dedicated mycologist for more than thirty years. He is the 1998 recipient of the Collective Heritage Institute's Bioneers Award and the 1999 recipient of the Founder of a New Northwest Award from the Pacific Rim Association of Resource Conservation and Development Councils. Stamets has written five books on mushroom cultivation, use, and identification and numerous articles and scholarly papers on medicinal, culinary, and psycho-active mushrooms. His books Growing Gourmet and Medicinal Mushrooms and The Mushroom Cultivator (co-author) have long been hailed as the definitive texts on mushroom cultivation. Excerpt. ® Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved. Part I THE MYCELIAL MIND There are more species of fungi, bacteria, and protozoa in a single scoop of soil than there are species of plants and vertebrate animals in all of North America. And of these, fungi are the grand recyclers of our planet, the mycomagicians disassembling large organic molecules into simpler forms, which in turn nourish other members of the ecological community. Fungi are the interface organisms between life and death. Look under any log lying on the ground and you will see fuzzy, cobweblike growths called mycelium, a fine web of cells which, in one phase of its life cycle, fruits mushrooms. This fine web of cells courses through virtually all habitats--like mycelial tsunamis--unlocking nutrient sources stored in plants and other organisms, building soils. The activities of mycelium help heal and steer ecosystems on their evolutionary path, cycling nutrients through the food chain. As land masses and mountain ranges form, successive generations of plants and animals are born, live, and die. Fungi are keystone species that create ever-thickening layers of soil, which allow future plant and animal generations to flourish. Without fungi, all ecosystems would fail. With each footstep on a lawn, field, or forest floor, we walk upon these vast sentient cellular membranes. Fine cottony tufts of mycelium channel nutrients from great distances to form fast-growing mushrooms. Mycelium, constantly on the move, can travel across landscapes up to several inches a day to weave a living network over the land. But mycelium benefits our environment far beyond simply producing mushrooms for our consumption. Humans collaborate with these cellular networks, using fungi, specifically using mushroom mycelium as spawn, for both short- and long-term benefits. Mushroom spawn lets us recycle garden waste, wood, and yard debris, thereby creating mycological membranes that heal habitats suffering from poor nutrition, stress, and toxic waste. In this sense, mushrooms emerge as environmental guardians in a time critical to our mutual evolutionary survival. I believe random selection is no longer the dominant force of human evolution. Our political, economic, and biotechnological policies may determine our future, for better or worse. Some forecasts claim that half of the current species could disappear in the next hundred years if current trends continue. A what-if Pentagon report issued in October 2003, An Abrupt Climate Change Scenario and Its Implications for United States National Security (Schwartz and Randall 2003), hypothesizes that a more dire and imminent collapse of our biosphere may occur as climates radically destabilize as a result of pollution and global warming. I wonder what would happen if there were a United Organization of Organisms (UOO, pronounced uh-oh), where each species gets one vote. Would we be voted off the planet? The answer is pretty clear. When we irresponsibly exploit the Earth, disease, famine, and ecological collapse result. We face the possibility of being rejected by the biosphere as a virulent organism. But if we act as a responsible species, nature will not evict us. Our fungal friends equip us with tools to act responsibly and repair our shared environment, leading the way to habitat recovery. So knowing how to work with fungi--by custom pairing fungal species with plant communities--is critical for our survival. The twenty-first century may be remembered as the Biotech Age, when these kinds of mycotechnologies play a prominent and increasing role in strengthening habitat health. CHAPTER 1 Mycelium as Nature's Internet I believe that mycelium is the neurological network of nature. Interlacing mosaics of mycelium infuse habitats with information-sharing membranes. These membranes are aware, react to change, and collectively have the long-term health of the host environment in mind. The mycelium stays in constant molecular communication with its environment, devising diverse enzymatic and chemical responses to complex challenges. These networks not only survive, but sometimes expand to thousands of acres in size, achieving the greatest mass of any individual organism on this planet. That mycelia can spread enormous cellular mats across thousands of acres is a testimonial to a successful and versatile evolutionary strategy. The History of Fungal Networks Animals are more closely related to fungi than to any other kingdom. More than 600 million years ago we shared a common ancestry. Fungi evolved a means of externally digesting food by secreting acids and enzymes into their immediate environs and then absorbing nutrients using netlike cell chains. Fungi marched onto land more than a billion years ago. Many fungi partnered with plants, which largely lacked these digestive juices. Mycologists believe that this alliance allowed plants to inhabit land around 700 million years ago. Many millions of years later, one evolutionary branch of fungi led to the development of animals. The branch of fungi leading to animals evolved to capture nutrients by surrounding their food with cellular sacs, essentially primitive stomachs. As species emerged from aquatic habitats, organisms adapted means to prevent moisture loss. In terrestrial creatures, skin composed of many layers of cells emerged as a barrier against infection. Taking a different evolutionary path, the mycelium retained its netlike form of interweaving chains of cells and went underground, forming a vast food web upon which life flourished. About 250 million years ago, at the boundary of the Permian and Triassic periods, a catastrophe wiped out 90 percent of the Earth's species when, according to some scientists, a meteorite struck. Tidal waves, lava flows, hot gases, and winds of more than a thousand miles per hour scourged the planet. The Earth darkened under a dust cloud of airborne debris, causing massive extinctions of plants and animals. Fungi inherited the Earth, surging to recycle the postcataclysmic debris fields. The era of dinosaurs began and then ended 185 million years later when another meteorite hit, causing a second massive extinction. Once again, fungi surged and many symbiotically partnered with plants for survival. The classic cap and stem mushrooms, so common today, are the descendants of varieties that predated this second catastrophic event. (The oldest known mushroom--encased in amber and collected in New Jersey--dates from Cretaceous time, 92 to 94 million years ago. Mushrooms evolved their basic forms well before the most distant mammal ancestors of humans.) Mycelium steers the course of ecosystems by favoring successions of species. Ultimately, mycelium prepares its immediate environment for its benefit by growing ecosystems that fuel its food chains. Ecotheorist James Lovelock, together with Lynn Margulis, came up with the Gaia hypothesis, which postulated that the planet's biosphere intelligently piloted its course to sustain and breed new life. I see mycelium as the living network that manifests the natural intelligence imagined by Gaia theorists. The mycelium is an exposed sentient membrane, aware and responsive to changes in its environment. As hikers, deer, or insects walk across these sensitive filamentous nets, they leave impressions, and mycelia sense and respond to these movements. A complex and resourceful structure for sharing information, mycelium can adapt and evolve through the ever-changing forces of nature. I especially feel that this is true upon entering a forest after a rainfall when, I believe, interlacing mycelial membranes awaken. These sensitive mycelial membranes act as a collective fungal consciousness. As mycelia's metabolisms surge, they emit attractants, imparting sweet fragrances to the forest and connecting ecosystems and their species with scent trails. Like a matrix, a biomolecular superhighway, the mycelium is in constant dialogue with its environment, reacting to and governing the flow of essential nutrients cycling through the food chain. I believe that the mycelium operates at a level of complexity that exceeds the computational powers of our most advanced supercomputers. I see the myce-lium as the Earth's natural Internet, a consciousness with which we might be able to communicate. Through cross-species interfacing, we may one day exchange information with these sentient cellular networks. Because these externalized neurological nets sense any impression upon them, from footsteps to falling tree branches, they could relay enormous amounts of data regarding the movements of all organisms through the landscape. A new bioneering science could be born, dedicated to programming myconeurological networks to monitor and respond to threats to environments. Mycelial webs could be used as information platforms for mycoengineered ecosystems. The idea that a cellular organism can demonstrate intelligence might seem radical if not for work by researchers like Toshuyiki Nakagaki (2000). He placed a maze over a petri dish filled with the nutrient agar and introduced nutritious oat flakes at an entrance and exit. He then inoculated the entrance with a culture of the slime mold Physarum polycephalum under sterile conditions. As it grew through the maze it consistently chose the shortest route to the oat flakes at the end, rejecting dead ends and empty exits, demonstrating a form of intelligence, according to Nakagami and his fellow researchers. If this is true, then the neural nets of microbes and mycelia may be deeply intelligent. A few recent studies support this novel perspective--that fungi can be intelligent and may have potential as our allies, perhaps being programmed to collect environmental data, as suggested above, or to communicate with silicon chips in a computer interface. Envisioning fungi as nanoconductors in mycocomputers, Gorman (2003) and his fellow researchers at Northwestern University have manipulated mycelia of Aspergillus niger to organize gold into its DNA, in effect creating mycelial conductors of electrical potentials. NASA reports that microbiologists at the University of Tennessee, led by Gary Sayler, have developed a rugged biological computer chip housing bacteria that glow upon sensing pollutants, from heavy metals to PCBs (Miller 2004). Such innovations hint at new microbiotechnologies on the near horizon. Working together, fungal networks and environmentally responsive bacteria could provide us with data about pH, detect nutrients and toxic waste, and even measure biological populations. Fungi in Outer Space? Fungi may not be unique to Earth. Scientists theorize that life is spread throughout the cosmos, and that it is likely to exist wherever water is found in a liquid state. Recently, scientists detected a distant planet 5,600 light-years away, which formed 13 billion years ago, old enough that life could have evolved there and become extinct several times over (Savage et al. 2003). (It took 4 billion years for life to evolve on Earth.) Thus far 120 planets outside our solar system have been discovered, and more are being discovered every few months. Astrobiologists believe that the precursors of DNA, prenucleic acids, are forming throughout the cosmos as an inevitable consequence of matter as it organizes, and I have little doubt that we will eventually survey planets for mycological communities. The fact that NASA has established the Astrobiology Institute and that Cambridge University Press has established The International Journal for Astrobiology is strong support for the theory that life springs from matter and is likely widely distributed throughout the galaxies. I predict an Interplanetary Journal of Astromycology will emerge as fungi are discovered on other planets. It is possible that proto-germplasm could travel throughout the galactic expanses riding upon comets or carried by stellar winds. This form of interstellar protobiological migration, known as panspermia, does not sound as farfetched today as it did when first proposed by Sir Fred Doyle and Chandra Wickramasinghe in the early 1970s. NASA considered the possibility of using fungi for interplanetary colonization. Now that we have landed rovers on Mars, NASA takes seriously the unknown consequences that our microbes will have on seeding other planets. Spores have no borders. The Mycelial Archetype Nature tends to build upon its successes. The mycelial archetype can be seen throughout the universe: in the patterns of hurricanes, dark matter, and the Internet. The similarity in form to mycelium may not be merely a coincidence. Biological systems are influenced by the laws of physics, and it may be that mycelium exploits the natural momentum of matter, just like salmon take advantage of the tides. The architecture of mycelium resembles patterns predicted in string theory, and astrophysicists theorize that the most energy-conserving forms in the universe will be organized as threads of matterenergy. The arrangement of these strings resembles the architecture of mycelium. When the Internet was designed, its weblike structure maximized the pooling of data and computational power while minimizing critical points upon which the system is dependent. I believe that the structure of the Internet is simply an archetypal form, the inevitable consequence of a previously proven evolutionary model, which is also seen in the human brain; diagrams of computer networks bear resemblance to both mycelium and neurological arrays in the mammalian brain (see figures 3 and 4). Our understanding of information networks in their many forms will lead to a quantum leap in human computational power (Bebber et al. 2007). Mycelium in the Web of Life As an evolutionary strategy, mycelial architecture is amazing: one cell wall thick, in direct contact with myriad hostile organisms, and yet so pervasive that a single cubic inch of topsoil contains enough fungal cells to stretch more than 8 miles if placed end to end. I calculate that every footstep I take impacts more than 300 miles of mycelium. These fungal fabrics run through the top few inches of virtually all landmasses that support life, sharing the soil with legions of other organisms. If you were a tiny organism in a forest's soil, you would be enmeshed in a carnival of activity, with mycelium constantly moving through subterranean landscapes like cellular waves, through dancing bacteria and swimming protozoa with nematodes racing like whales through a microcosmic sea of life. Year-round, fungi decompose and recycle plant debris, filter microbes and sediments from runoff, and restore soil. In the end, life-sustaining soil is created from debris, particularly dead wood. We are now entering a time when mycofilters of select mushroom species can be constructed to destroy toxic waste and prevent disease, such as infection from coliform or staph bacteria and protozoa and plagues caused by disease-carrying organisms. In the near future, we can orchestrate selected mushroom species to manage species successions. While mycelium nourishes plants, mushrooms themselves are nourishment for worms, insects, mammals, bacteria, and other, parasitic fungi. I believe that the occurrence and decomposition of a mushroom pre-determines the nature and composition of down-stream populations in its habitat niche. Wherever a catastrophe creates a field of debris--whether from downed trees or an oil spill--many fungi respond with waves of mycelium. This adaptive ability reflects the deep-rooted ancestry and diversity of fungi--resulting in the evolution of a whole kingdom populated with between 1 and 2 million species. Fungi outnumber plants at a ratio of at least 6 to 1. About 10 percent of fungi are what we call mushrooms (Hawksworth 2001), and only about 10 percent of the mushroom species have been identified, meaning that our taxonomic knowledge of mushrooms is exceeded by our ignorance by at least one order of magnitude. The surprising diversity of fungi speaks to the complexity needed for a healthy environment. What has been become increasingly clear to mycologists is that protecting the health of the environment is directly related to our understanding of the roles of its complex fungal populations. Our bodies and our environs are habitats with immune systems; fungi are a common bridge between the two. All habitats depend directly on these fungal allies, without which the life-support system of the Earth would soon collapse. Mycelial networks hold soils together and aerate them. Fungal enzymes, acids, and antibiotics dramatically affect the condition and structure of soils (see page 18). In the wake of catastrophes, fungal diversity helps restore devastated habitats. Evolutionary trends generally lead to increased bio-diversity. However, due to human activities we are losing many species before we can even identify them. In effect, as we lose species, we are experiencing devolution--turning back the clock on biodiversity, which is a slippery slope toward massive ecological collapse. The interconnectedness of life is an obvious truth that we ignore at our peril. In the 1960s, the concept of better living through chemistry became the ideal as plastics, alloys, pesticides, fungicides, and petrochemicals were born in the laboratory. When these synthetics were released into nature, they often had a dramatic and initially desirable effect on their targets. However, events in the past few decades have shown that many of these inventions were in fact bitter fruits of science, levying a heavy toll on the biosphere. We have now learned that we must tread softly on the web of life, or else it will unravel beneath us. Toxic fungicides like methyl bromide, once touted, not only harm targeted species but also nontargeted organisms and their food chains and threaten the ozone layer. Toxic insecticides often confer a temporary solution until tolerance is achieved. When the natural benefits of fungi have been repressed, the perceived need for artificial fertilizers increases, creating a cycle of chemical dependence, ultimately eroding sustainability. However, we can create mycologically sustainable environments by introducing plant-partnering fungi (mycorrhizal and endophytic) in combination with mulching with saprophytic mushroom mycelia. The results of these fungal activities include healthy soil, biodynamic communities, and endless cycles of renewal. With every cycle, soil depth increases and the capacity for biodiversity is enhanced. Living in harmony with our natural environment is key to our health as individuals and as a species. We are a reflection of the environment that has given us birth. Wantonly destroying our life-support ecosystems is tantamount to suicide. Enlisting fungi as allies, we can offset the environmental damage inflicted by humans by accelerating organic decomposition of the massive fields of debris we create--through everything from clear-cutting forests to constructing cities. Our relatively sudden rise as a destructive species is stressing the fungal recycling systems of nature. The cascade of toxins and debris generated by humans destabilizes nutrient return cycles, causing crop failure, global warming, climate change and, in a worst-case scenario, quickening the pace towards ecocatastrophes of our own making. As ecological disrupters, humans challenge the immune systems of our environment beyond their limits. The rule of nature is that when a species exceeds the carrying capacity of its host environment, its food chains collapse and diseases emerge to devastate the population of the threatening organism. I believe we can come into balance with nature using mycelium to regulate the flow of nutrients. The age of mycological medicine is upon us. Now is the time to ensure the future of our planet and our species by partnering, or running, with mycelium.

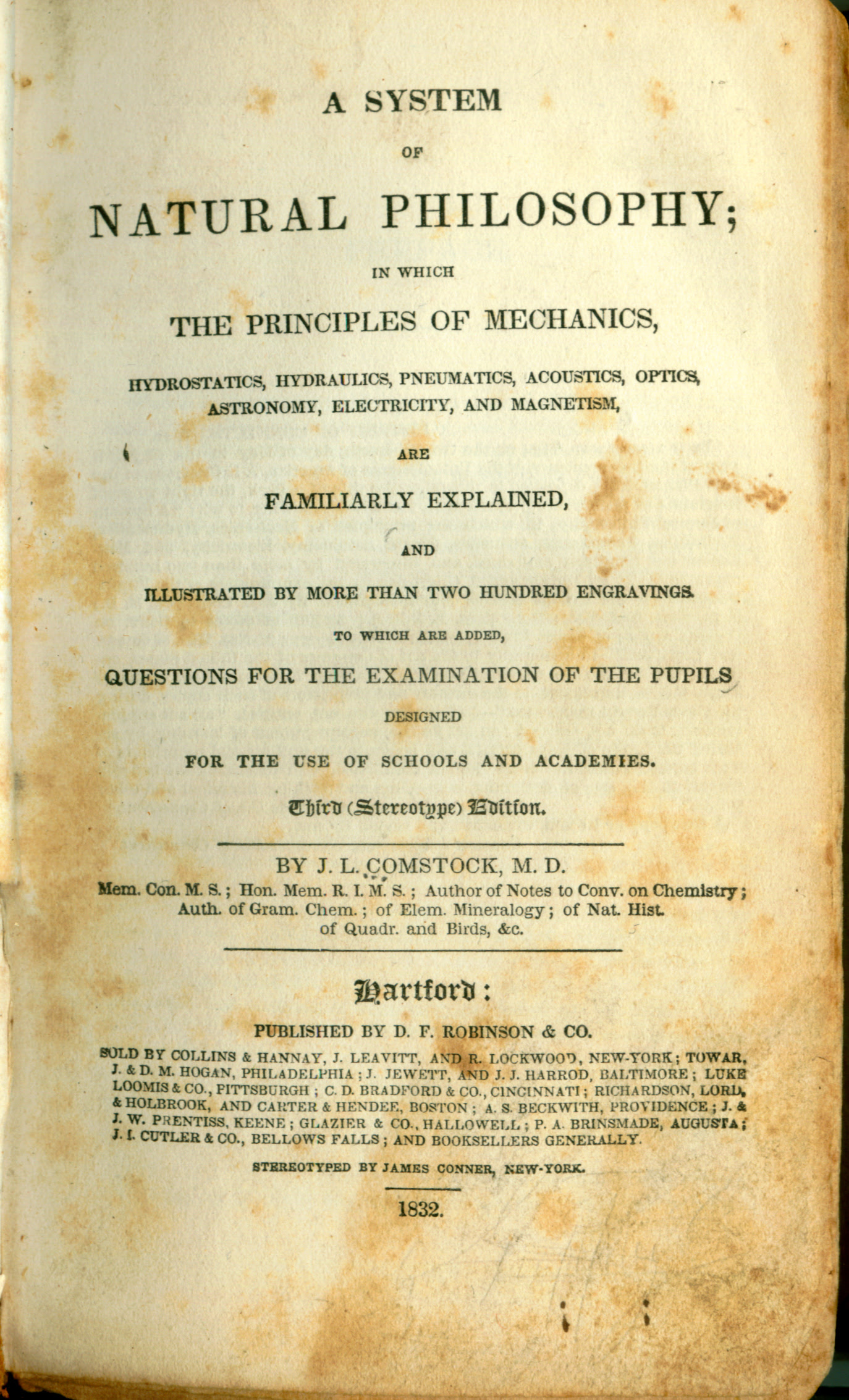

Publication Details

Title:

Author(s):

Illustrator:

Binding: Paperback

Published by: Ten Speed Press: , 2005

Edition:

ISBN: 9781580085793 | 1580085792

356 pages.

Book Condition: Very Good

Pickup currently unavailable at Book Express Warehouse

Product information

New Zealand Delivery

Shipping Options

Shipping options are shown at checkout and will vary depending on the delivery address and weight of the books.

We endeavour to ship the following day after your order is made and to have pick up orders available the same day. We ship Monday-Friday. Any orders made on a Friday afternoon will be sent the following Monday. We are unable to deliver on Saturday and Sunday.

Pick Up is Available in NZ:

Warehouse Pick Up Hours

- Monday - Friday: 9am-5pm

- 62 Kaiwharawhara Road, Wellington, NZ

Please make sure we have confirmed your order is ready for pickup and bring your confirmation email with you.

Rates

-

New Zealand Standard Shipping - $6.00

- New Zealand Standard Rural Shipping - $10.00

- Free Nationwide Standard Shipping on all Orders $75+

Please allow up to 5 working days for your order to arrive within New Zealand before contacting us about a late delivery. We use NZ Post and the tracking details will be emailed to you as soon as they become available. Due to Covid-19 there have been some courier delays that are out of our control.

International Delivery

We currently ship to Australia and a range of international locations including: Belgium, Canada, China, Switzerland, Czechia, Germany, Denmark, Spain, Finland, France, United Kingdom, United States, Hong Kong SAR, Thailand, Philippines, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Sweden & Singapore. If your country is not listed, we may not be able to ship to you, or may only offer a quoting shipping option, please contact us if you are unsure.

International orders normally arrive within 2-4 weeks of shipping. Please note that these orders need to pass through the customs office in your country before it will be released for final delivery, which can occasionally cause additional delays. Once an order leaves our warehouse, carrier shipping delays may occur due to factors outside our control. We, unfortunately, can’t control how quickly an order arrives once it has left our warehouse. Contacting the carrier is the best way to get more insight into your package’s location and estimated delivery date.

- Global Standard 1 Book Rate: $37 + $10 for every extra book up to 20kg

- Australia Standard 1 Book Rate: $14 + $4 for every extra book

Any parcels with a combined weight of over 20kg will not process automatically on the website and you will need to contact us for a quote.

Payment Options

On checkout you can either opt to pay by credit card (Visa, Mastercard or American Express), Google Pay, Apple Pay, Shop Pay & Union Pay. Paypal, Afterpay and Bank Deposit.

Transactions are processed immediately and in most cases your order will be shipped the next working day. We do not deliver weekends sorry.

If you do need to contact us about an order please do so here.

You can also check your order by logging in.

Contact Details

- Trade Name: Book Express Ltd

- Phone Number: (+64) 22 852 6879

- Email: sales@bookexpress.co.nz

- Address: 62 Kaiwharawhara Rd, Kaiwharawhara, Wellington, 6035, New Zealand.

- GST Number: 103320957 - We are registered for GST in New Zealand

- NZBN: 9429031911290

We have a 30-day return policy, which means you have 30 days after receiving your item to request a return.

To be eligible for a return, your item must be in the same condition that you received it, unworn or unused, with tags, and in its original packaging. You’ll also need the receipt or proof of purchase.

To start a return, you can contact us at sales@bookexpress.co.nz. Please note that returns will need to be sent to the following address: 62 Kaiwharawhara Road, Wellington, NZ once we have confirmed your return.

If your return is accepted, we’ll send you a return shipping label, as well as instructions on how and where to send your package. Items sent back to us without first requesting a return will not be accepted.

You can always contact us for any return question at sales@bookexpress.co.nz.

Damages and issues

Please inspect your order upon reception and contact us immediately if the item is defective, damaged or if you receive the wrong item, so that we can evaluate the issue and make it right.

Exceptions / non-returnable items

Certain types of items cannot be returned, like perishable goods (such as food, flowers, or plants), custom products (such as special orders or personalized items), and personal care goods (such as beauty products). We also do not accept returns for hazardous materials, flammable liquids, or gases. Please get in touch if you have questions or concerns about your specific item.

Unfortunately, we cannot accept returns on sale items or gift cards.

Exchanges

The fastest way to ensure you get what you want is to return the item you have, and once the return is accepted, make a separate purchase for the new item.

European Union 14 day cooling off period

Notwithstanding the above, if the merchandise is being shipped into the European Union, you have the right to cancel or return your order within 14 days, for any reason and without a justification. As above, your item must be in the same condition that you received it, unworn or unused, with tags, and in its original packaging. You’ll also need the receipt or proof of purchase.

Refunds

We will notify you once we’ve received and inspected your return, and let you know if the refund was approved or not. If approved, you’ll be automatically refunded on your original payment method within 10 business days. Please remember it can take some time for your bank or credit card company to process and post the refund too.

If more than 15 business days have passed since we’ve approved your return, please contact us at sales@bookexpress.co.nz.